Study Explains Increased Risk of TB for Smokers

Posted on: 24 March 2016

What better way to mark World TB Day (today, March 24) than with another significant research finding from Trinity’s Professor in Respiratory Medicine, Joe Keane?

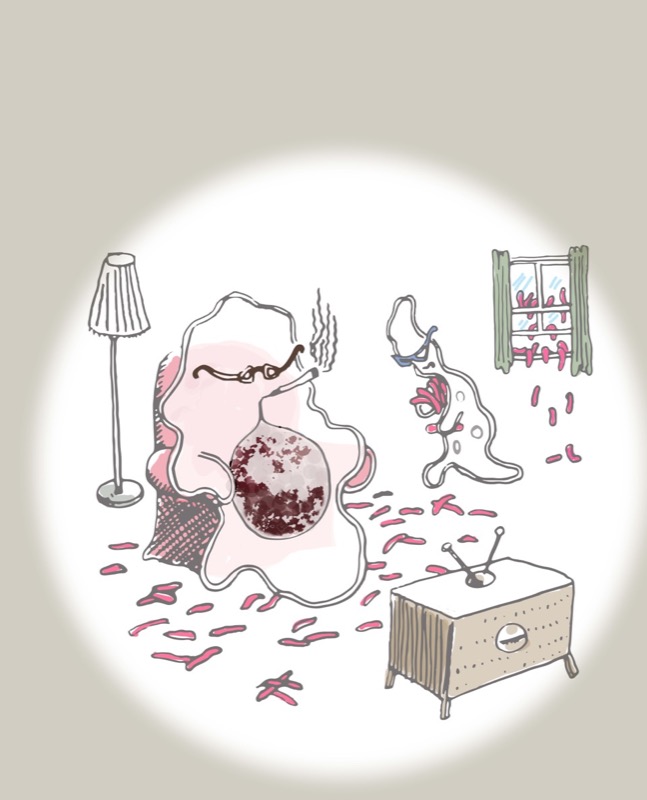

This latest study shows that smoking increases an individual’s risk of developing tuberculosis (TB) because it causes vital immune cells to become clogged up, slowing their movement and impeding their ability to fight infection.

Trinity’s Dr Seonadh O’Leary and Dr Mary O’Sullivan conceptualised and performed the human research in this important paper.

The study, which was done in collaboration with the University of Cambridge’s Department of Medicine, has just been published in the journal Cell.

TB is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that primarily infects the lungs, but can also infect other organs. It is transmitted from person to person through the air. The disease can cause breathlessness, wasting, and eventual death.

For people exposed to TB, the biggest risk factor for infection is exposure to smoke, including active and passive cigarette smoking and smoke from burning fuels. This risk is even greater than co-infection with HIV. However, until now it has not been clear why smoke should increase this risk.

Commenting on the findings, Professor Keane, based at St James's Hospital, said: “TB kills 4,000 people every day, and there are around eight million TB cases worldwide. Cigarette smoking is one of the biggest contributors to developing the disease. It is estimated that 15% of all cases arise from the effects of smoking, and until now we didn't really know why, or how, smoking had such a profound effect.

“Our partner in this research paper, Professor Lalita Ramakrishnan, and her team in the University of Cambridge, identified a very interesting finding in a zebrafish model of the disease.”

Professor Ramakrishnan said: “We found that a type of immune cell called a macrophage, which is a white blood cell that is supposed to attack and engulf foreign material that gets inside the body, was not able to travel to the TB infection after it had been exposed to particles similar to those you get in tobacco smoke. We then approached Professor Keane to see if they could discover if this same effect occurred in human lungs.”

Professor Keane runs one of only a handful of laboratories in the world where such research on human cells could be conducted.

“We took tissue samples from smokers who attended the bronchoscopy suite in St James's Hospital and found that smokers’ lungs were full of cells that looked abnormal because material from tobacco smoke goes into the white cells and gets trapped there,” said Professor Keane.

“White blood cells with this debris inside them were unable to move towards the invading TB bacteria. This migration is a necessary first step for the body to fight TB, and if it can't do that, then the person is more likely to develop the disease.”

The findings could also have significance for people who inhale indoor air pollution. More than one third of the world’s population cooks indoors without a chimney and gets exposed to an excessive amount of biomass fuel smoke. This material also makes the patient susceptible to TB (accounting for 22% of cases), which is extremely common in the developing world.

The research was supported by the Health Research Board of Ireland and The Royal City of Dublin Hospital Trust.