Inflation: why it’s happening and why interest rates are going up to combat it

Posted on: 05 August 2022

Supriya Kapoor, Assistant Professor of Finance at Trinity, writes an explainer piece about a pertinent topic, first published by The Conversation.

Supriya Kapoor, Trinity College Dublin

Soaring prices have forced central banks in many developed countries to raise their interest rates in recent weeks. These organisations are in charge of attempts to rein in rising costs that are threatening to wreak havoc on household budgets in coming months.

Western economies are currently experiencing two major shocks that are pushing up the costs of goods and services. First, the war in Ukraine has resulted in surging energy and food prices. Second, there has been record-high industrial goods inflation due to sluggish supply in response to COVID-19.

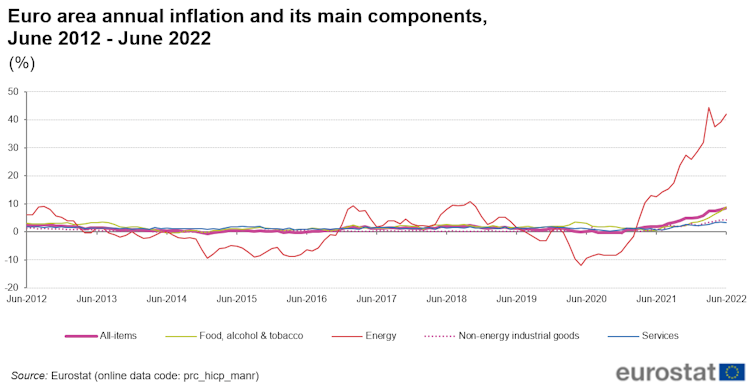

The graph below shows the main components of inflation in the Euro area. All items are rising but energy has seen the highest annual inflation rate (42% in June 2022), followed by food. High food and energy prices are trickling down to real incomes, leading to a drop in households’ expectations of their financial situation. Businesses are also suffering due to supply shortages and high energy prices.

At the same time, growth has been picking up due to the post-lockdown reopening of the economy, high amounts of accumulated household savings and fiscal support to offset high energy prices. It’s a broadly similar picture in the UK and it’s safe to say that inflation today is being imported from outside both economies.

As a result, the Bank of England has implemented its biggest hike in nearly 30 years in August, bringing UK rates to 1.75%. Before that, the US Federal Reserve increased its base rate for a third time this year, implementing its second 0.75% rise on July 27. The ECB made its biggest rate change in more than a decade on July 21 when it raised rates by half a percentage point, defying market expectations of a quarter-point rise.

A quarter of a percentage point change may not sound like much but these moves are designed to tweak the economy while maintaining a balance between preventing inflation (when prices increase and people’s money cannot buy as much) and maintaining economic growth. Central banks do this by trying to bring inflation into line with their “price stability” targets, which for the ECB and the Bank of England means 2% inflation, for example.

Central bank tools

The recent rate increases are also part of central banks’ plans to “normalise” monetary policy following strategies used to stem the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. Together with the subsequent euro area sovereign debt crisis, the financial crisis devastated many households, businesses and banks.

In response, the ECB launched its unconventional monetary policy in 2013. It wanted to try to return inflation to levels consistent with its price stability target of 2% and incentivise banks to lend to businesses as a way to boost the economy after the downturn. This involved the use of tools including:

- forward guidance, when the central bank openly discusses market expectations of future levels of interest rates

- negative interest-rate policy, setting target nominal interest rates below 0%

- targeted long-term refinancing operations, providing cheap financing to lenders

- asset purchase programmes, when the central bank buys assets such as government bonds, corporate bonds, and asset-backed securities.

And it wasn’t just the ECB. Other central banks including the Bank of England and US Federal Reserve reacted by boosting liquidity to the banking sector and aggressively lowering interest rates.

The Bank of Japan has adopted similar measures since the early 2000s, following its own house and stock price crashes. Central banks also used quantitative easing to jumpstart their economies following the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Getting back to normal

These days, the most recent central bank decisions reflect changing strategies in response to a new economic picture, particularly in relation to some central bank expectations that inflation will remain high for some time. They hope that current efforts to normalise monetary policy following the use of the post financial crisis tools discussed above and the absence of new disruptions will help global supply bottlenecks ease and energy costs stabilise. This should push inflation back towards their targets.

But balance is key. When it comes to the direct impact of these moves, increases in interest rates will create higher mortgage repayments, especially for new borrowers as well as those on tracker mortgages or variable rates. This will mean people have less money to spend elsewhere. Increasing inflation – and therefore uncertainty about the future – can also lead to reduced consumer and business confidence, dragging down household and business spending even further.

One bright spot for the economy at the moment is the strength of the labour market. There are employment opportunities in many sectors and employer demand for labour is robust.

But high employment also means people have more money to spend and this risks creating excess demand, which would add to inflation. To guard against this outcome, governments could target increased public spending on sectors in dire need, while also addressing cost of living pressures alongside central banks.

And for business, as they continue to face high costs and supply chain disruptions, diversifying away from more than one supply location could help bring down costs and feed through to prices for consumers.

Current expectations are that inflation will remain undesirably high for some time. Central bank decision-making will play a major role in striking the balance needed to bring down the cost of living without stalling the economy.![]()

Supriya Kapoor, Assistant Professor of Finance, Trinity College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.